Donna Halper is an American treasure best known for discovering a Canadian gem.

Ask any fan of the Hall of Fame rock band Rush, and they’ll tell you Donna helped send the Toronto trio of Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and (eventually) Neil Peart on their way to a 40-plus year journey simply by putting the needle down on a song called Working Man as a deejay and music director of WMMS radio in Cleveland in 1974.

That in itself would be an accomplishment worth celebrating, but in her 74 years on Earth, Donna Halper has been and continues to be a teacher, a mentor, a media historian, a writer (including much in the way of sports writing, including for the Society for American Baseball Research), a friend, and overall, a gentle soul.

Her research and writing about a Black football player from Boston College and his exclusion from the 1940 Cotton Bowl won her the Jinx Coleman Broussard Award for Excellence in the Teaching of Media History, given by the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. Donna is associate professor of media studies at Lesley University in Cambridge, Mass.

As a Rush fan since 1975 (first concert May 28, 1976, at the Riviera Theatre in Chicago) and an admirer of Donna Halper from afar for many years, I wanted to get her insights on Rush and their genius and their legacy. She was more than generous with her time for this interview.

The following Q and A has been edited for brevity.

Question: You have been known as the deejay who discovered Rush. But you are many other things: professor, writer, historian, woman of faith. But if discovering Rush is your epitaph, is that a cool thing?

Donna Halper: That would be cool, but it would also minimalize a lot of the other things I’ve done over the years. And I’m not, “Oh, don’t you know who I am?” But X number of years from now, people are going to be like, “Who’s Rush?” I’d like to be known as somebody who made a difference on some small level. Maybe I changed someone’s life. Maybe I made someone happy. Put on my tombstone: “She came. She saw. She kicked some butt.”

They (Rush) weren’t with a big label. They weren’t famous. They didn’t have a ton of money. They were just three working-class kids. I was a working-class kid. OK, I had the additional baggage of gender and being a Jew at a time when anti-Semitism was still out in the open. But I really related to the fact that these kids were just trying to live their dream. And as a music director, I just wanted to help. I never thought I’d meet them. I never thought we’d become friends. I never thought I’d be in touch with them like 48 years later. I was just thinking, “I want to give them a chance.”

If Rush had bombed, I’m not sorry I gave them a chance. I’m sorry it didn’t work out. I’m sorry you didn’t think they were as good as I did. But at least I know I tried. That’s why I felt giving them a chance was a really good thing. When I did it, I never realized the lasting repercussions it would have. That’s kind of cool when you think about it.

Q.: Had you listened to Working Man and the Rush album before you played it for the first time?

A.: Of course. When I was sent my first copy of the album, I did what music directors do. I dropped the needle. First of all, it’s been widely misinterpreted about “the bathroom song.” Everything was live. We had to find long songs in case the deejay had to go to the bathroom. But they had to be good songs. It wasn’t just, “Oh, it’s a long song, we’ll play it.” It couldn’t be a long piece of garbage. So I was looking for long songs but also good songs. It was all vinyl back in those days. You had a turntable in your office. They brought me up the new records, and one of them was in an envelope from A&M of Canada. I’m like, “Why is A&M of Canada sending me a record?” Usually, A&M in the United States signs a band and then they do a tour all over the world, including Canada. But it was a friend of mine who I had worked with in the past named Bob Roper. He sent me the record because his label had passed on them. But he thought they had some potential. He had seen them in a club. He sent his copy down to me. I auditioned it as music directors did. We marked the cuts we thought they (the deejays) ought to play, that were the best cuts on the album. I found Working Man. I found Finding My Way. Absolutely I had heard the record. That’s how I knew to advocate for it.

Q.: What in your opinion is the genius of Rush?

A.: The fact that they are constantly willing to reinvent themselves. That first record, and a lot of people like to mock it because it wasn’t fancy and schmancy and it didn’t have elegant lyrics. It wasn’t designed to be. It was designed to be for a club and bar audience because that’s who they were playing for. But even then they knew that’s not what they wanted. They knew that was a step along the way. It’s like I always say to people: “Were you born walking and talking? Nope.” But you still had to get through those stages to be where you are. If John Rutsey (original drummer replaced by Neil Peart), who by the way was not that bad a drummer … when I think of Rutsey, I think of Ringo Starr. Ringo had a chance to develop. Rutsey never did. Rutsey was exactly what they needed him to be. But if given the chance, I have the feeling he would have been able to take it to the next level.

The problem, though, is that he wasn’t a lyricist. They needed a lyricist. They knew it. Fortunately for them and unfortunately for John Rutsey, because of his health problems, they were able to find Neil out of all the people they auditioned. Neil not only could play the kind of drums they wanted, but he was able to take them to the next level. They were always willing to take chances. The genius of this band is that you can listen to all of their albums. They never sound like, “Oh, those guys just mailed it in; they’ve got a thing they do and they do it album after album after album.” And you’re sitting there like, “Oh, my God, can’t they do something else?” I think of Rush the way I think of the Beatles. Now, I’m not comparing them. I don’t want people with their hair on fire. I am saying that the Beatles at the beginning were “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah.” But by the end, you’re talking some of the most creative, innovative, interesting music that was being made at the time with lyrics that made you sit there and go, “I wish I had said that.” I think Rush had that ability and that capability. And they did that. They were able to transform themselves a multitude of times. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes it didn’t work. But it never stopped them from trying. They were always willing to take risks. They were always willing to try something new.

Q.: The follow-up to that is that they brought their audience along with them. Some people said, “I like Hemispheres,” and they jumped off after Rush started doing shorter songs. But for the most part, the people who were with them in the ‘70s stayed with them until the 20-teens. That’s quite a feat, isn’t it?

A.: That’s why I’m doing this Deep Dive every month. That’s why I think the Deep Dive webcast is so interesting. We’re taking albums with tracks on them that may have been overlooked, that may have been forgotten or may have been subsumed by, “This is the greatest track on the record!” Everybody knows Limelight. Everybody knows Tom Sawyer. Everybody knows Spirit of Radio. But what else is on the album? So it gives me a chance to go back to my music-director’s days. OK, we’ve got the hit, but what else is on the album? I really think there are a lot of tracks on Rush albums that haven’t gotten the airplay they deserve. And maybe people need to refamiliarize themselves with those songs. The band was always trying to put out interesting records. A lot of people look at Rush lyrics like the soundtrack of their lives. They look at things that Neil wrote like, “Yeah, that speaks for me.” There are certain threads and certain themes that run through their work but how they represent it is different from decade to decade, making their music fresh all over again.

Q.: What are your favorites of the albums and/or songs?

A.: Can’t do it. I can’t do it, and I’ll tell you why. I’ve never had kids. That was my choice. Rush are kind of like my kids. I’m thinking like, “Wow, isn’t it great what my kids have done?” Are there certain songs that resonate with me more than others? Sure. But I don’t think like “favorites.” The reality is these are my friends. At first they needed a big sister, so I was their big sister. Then they struck out on their own. They went out into the world, and they were perfectly fine. So I became their friend and to some degree their mentor and an advocate. I did a lot of behind-the-scenes stuff that a lot of people don’t know. I defended them to critics. But never thought about, “What is my favorite song?” I just thought about, “Isn’t it great that my friends are out there doing such great music? God bless ‘em.” And to this day, when I hear a Rush song on the radio, I’m like, “Yeah. I’m so proud of them.”

Q.: Could what you did with discovering them happen today?

A.: No, it couldn’t. In my opinion, and I could be wrong, the worst thing that happened to my industry was the Telecommunications Act of 1996. The reason it was the worst was not just because – disclaimer – I lost my job, me and 20,000 other people because as the media consolidated, six giant conglomerates bought up most of the stations, which encouraged voice tracking, which encouraged more syndication and less localism. And the independence of the music director of the program director got taken away. Yes, there are some stations that are live and local. But much fewer. Now radio’s just one other choice. There’s podcasts. There’s YouTube. Radio is no longer king. I wrote an article for Radio World a few months ago. What I wrote was, “Where does radio go from here?”

Years ago, I would ask students, “How many of you would like to be deejays?” And just about every hand would go up. Gradually fewer and fewer and fewer. Today, none. When I was a kid, I couldn’t imagine a better job than rock-and-roll deejay. Kids today, all they tell me is, “Yeah, the only time I listen to radio is if it’s on when my parents are in their car.” I think that’s profoundly sad. I think we allowed a bunch of giant conglomerates to eliminate one reason people listen – because it’s live and it’s local. I still think the cities that do live and local radio are doing the right things, and they are creating bonds with their audience. What the Telecommunications Act ended up doing, in my case, was I had to reinvent myself. I went back to school at the age of 55. I got my Ph.D. when I was 64. I’m still out there. I’m still teaching full time at the age of 74 because I want to. I can’t imagine retiring. I will write. I still do speaking engagements. I like to be active. I’m a cancer survivor. Every day is a gift. But what I don’t get to do is be on the air.

I miss radio every day of my life. And I hate what has happened to it because that liveness, that localism, that creativity, that inventiveness is gone. You could discover new bands. You could make a difference in the lives of your audience. Your audience bonded with you. Today, kids don’t want to listen to 18 minutes of commercials. They don’t want to hear the same 10 songs over and over. They can create their own playlist. They don’t need us anymore.

Could I discover Rush today? Sure. But I would have to do it in an entirely different way because radio is no longer the mass medium with the power. Times change. You’ve got to adapt. I adapted. I went back to school and got a Ph.D. The fact is radio needs to adapt. It needs to reach out to that younger audience. During the pandemic, radio listening went up hugely because people were stuck in their house. Will radio ever go back to the power it had? Nah, that ship has sailed. But can we still be a factor in people’s lives? Can we still discover new bands? Can we still befriend the audience as deejays? Yes, we can. Will we? I don’t know. My phone ain’t ringing. Could I do it again? Sure! Could I still be a good deejay? Yes, I could. I still think I have the voice. It’s not about me. It’s about new and up and coming people who need to be apprenticed into the possibilities of radio.

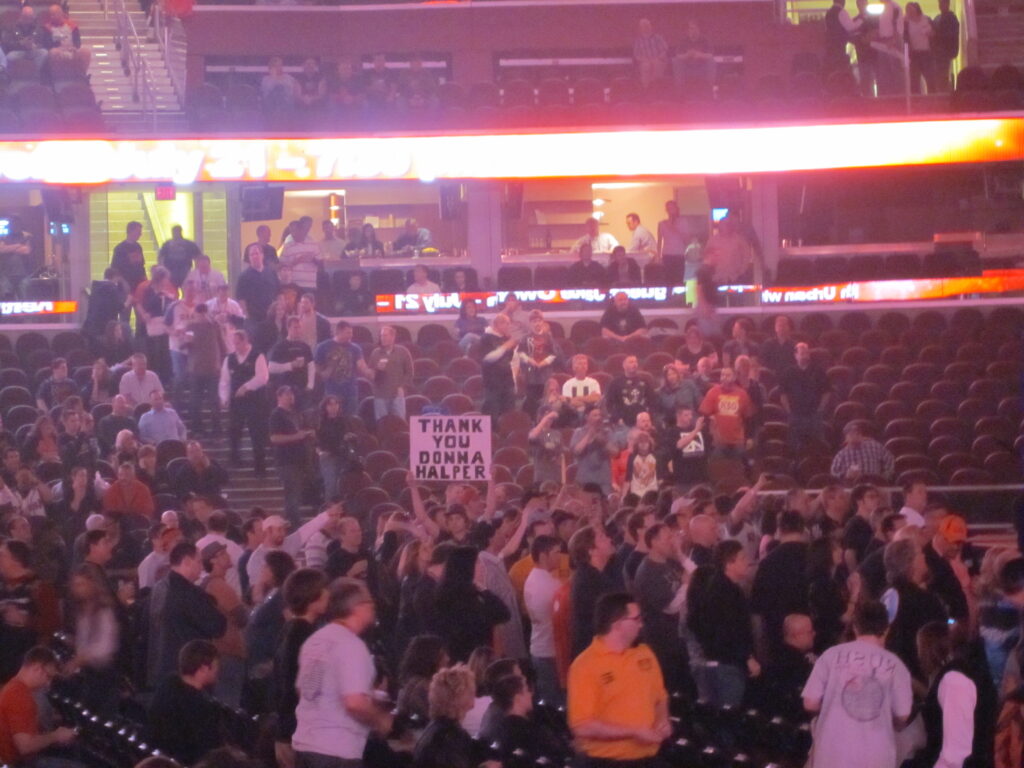

Q.: What does it mean to you that the band members and Rush fans remember your role in all of this?

A.: First of all, it was a surprise. And I’m not saying that like a humble brag. It was a surprise. I was a music director for more than 20 years. I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of people who thanked me. And it’s not like I expected it. I didn’t expect a marching band. It was my job. I was kind of Zen about the whole thing. I was going to do the best I can for my audience. I’m going to put out the best kinds of music that I can find on this record. If they like it, terrific. I did my job. If they don’t like it, I still did my job. I tried my best.

I never expected to be thanked. When I played Rush and their management was totally surprised because they couldn’t get arrested up in Toronto, but in Cleveland, suddenly they’re a big hit. I wanted to make sure that they got every chance. But I didn’t expect anything from it. I’m a music director. It’s what I do. When they put my name on that first Rush album and also on the second one (Fly By Night), I was like, “Wow.”

These are just nice people. So I just looked at it like, “Wow. That was really nice.” They didn’t have to do that. People ask me sometimes, “Did you get a finder’s fee?” No, I got a 45-year friendship. How lucky am I?” I never realized that I would be part of this international Rush fan base, this international community, that I’d be asked to speak at conferences. And I also never expected more than four decades later I’d still be having these kinds of conversations. I feel in many ways Rush changed my life. Rush changed my life differently from how Rush changed the fans’ lives. For the fans, it was like, “Oh my God, it’s Rush!” In my case, it’s like, I’m backstage hanging out with three by now really famous musicians. I was a working-class kid from Dorchester, Mass. Nobody expected that I would be anything.

All of these things, and yet, years later fast-forward, I’m hanging with Bruce Springsteen. I’m hanging with Bob Seger. I’m hanging with Rush. And I never sold out my ethics. And I never stopped being who I was. I got raised with a certain sense of ethics. I taught Sunday school for many years. Not like I think I’m so great. Not like I’m so holy. I’m not even terribly religious. But ethics matter to me. And it was very nice to find a rock band who believed in ethics. So we had some great conversations that were very different from the kinds of conversations you might have with some bands. Neil and I one time were hanging out talking about Shakespeare. How often do you get to do that?

So yeah, it’s been very gratifying and very surprising because I don’t want to be known for only that one thing, I feel honored that I am a part of that thing. And I probably wouldn’t even be talking to you if it weren’t for that thing. So yeah, it’s been surprising, gratifying. I never asked for it. But the fact that it is, it’s just a real blessing to me, and I’m just so appreciative.

Q.: Is it somewhat delicious that a woman discovered Rush in the U.S., given the impression that Rush doesn’t appeal to women, or hadn’t for many years?

A.: The thing about being female and not being a Rush fan: horse-pucky. There have always been female Rush fans. Were there a lot of them? We’ll never know because back in those early days, a lot of hard rock was really gendered space. It was basically expected that metal music would attract a bunch of guys. I have the feeling that some women might be like, “I wouldn’t be welcome here, so I’ll just listen at home.” I don’t think we’ll really know how many women fans there were, but I’ll tell you, I heard from a lot of them. When I was a music director, I absolutely heard from women Rush fans. It is probably true statistically that in the early days it was about 90-10, 90 percent guys, 10 percent ladies. That’s not where it is today. Not at all. I would say that about 35 percent of Rush fans are female, if not higher. I base this on conference attendance. I base this on fan events.

Q.: We lost Geddy Lee’s mother recently. Can you think of anyone who endured and overcame so much yet lived a full and rich life as she did?

A.: I don’t think we can compare anybody to what Geddy’s mom went through. How many of us are Holocaust survivors? What I think is inspiring about all the parents of Rush – Geddy’s parents, Alex’s, Neil’s — we lost Neil last year and we just lost his dad. All of the parents of this band had to let their kids go out into an uncertain world. If you have kids, you have certain dreams for them. But you want to keep them close. When the kids are young, the parents can have some kind of influence. But at a certain point, you’ve got to let them go. At a certain point, Neil’s dad may have really, really wanted him to work in the parts department. But that wasn’t Neil’s dream. His heart was in music.

Geddy’s mother absolutely wanted him to graduate from high school and go to college. When it became really obvious that his dream was to be a rock musician, she made him promise that if he had kids, those kids would go to college. And he kept that promise. Both of his kids are college graduates, a son with a Ph.D. and his daughter has at least a master’s. Geddy’s mother became his biggest fan. She wasn’t raised to be rock fan. She didn’t know her son was going to be famous, and she certainly didn’t know she was going to like rock and roll. But she became one of his biggest fans. And I give her props for that.

She was also a master of reinvention. She lost her husband. She opened a store. Whatever it took, that woman overcame. She lived a long life. She got to see her son be a success. She got to see all of her children be successful. I’m glad I got to meet Geddy’s mom. She was an amazing person. I’m glad I speak some Yiddish. I was able to speak some Yiddish with her. That really made her feel good. I’m sorry she passed, but I’m glad she lived such a long and interesting life.

Q.: I asked you about the genius of Rush. What is their legacy?

A.: They changed a lot of people’s lives. They really did. Can you say anything more than that? There are a lot of rock bands, and I’m not saying Rush were the only ones. If you’ve been involved with rock and roll, whether as a fan or as a music director, program director or as a musician, there are bands that, “Yeah, I’m glad I listened to them when I was growing up, and I haven’t thought about them in years.” And there are other bands that it’s, “Oh, my God, I just heard them on the radio or heard them on a podcast and it’s, ‘I haven’t thought about them in a long time. They still sound OK.’” And then there are other bands that are kind of like the soundtrack of your life, that when you hear those songs, they just stay. It takes you back to a time, a place, people you were with, what you saw, who you were.

I think Rush are like that for a lot of people. When I say “who you were,” it’s the different stages of your life. Rush changed people’s lives. So did a number of other bands. But the vast majority of what’s out there, it’s just pleasant and forgettable. I think to the worldwide community of Rush fans, those guys are not forgettable. Those guys are legendary. Those guys kept people going. They inspired them. They encouraged them. They articulated how people were feeling. They helped us get through. And for that, I think we are all grateful.

Great interview with Donna. Donna was one of our most respected music directors back when radio and records had a wonderful symbiotic relationship. That relationship, is long gone and Donna’s lament about radio is true.

I was privileged to work in the record side in National promotion for both Capitol and then MCA Records and during that time, I wish we had more people like Donna!

Amen to everything you said.

Dr. Halpert is a wonderful human. Music lover. Educator. Writer. Activist. One never knows how one act of kindness can change the world. She truly walks the walk.

I as a 50’s and 60’s musician agree with Donna Radio was and will be remembered as a way of life alive and the teens spent many hours in a day listening to their favorite DJ on their local radio station. I still play in a Rock Revival Band at 78 yrs old and enjoy taking the older generation back to when they were teens their music is like an old friend that they just meet once more.

Nicely put. Thank you for the comment.